Privacy and data protection are cornerstones of good governance, which most companies view as very important and embrace.

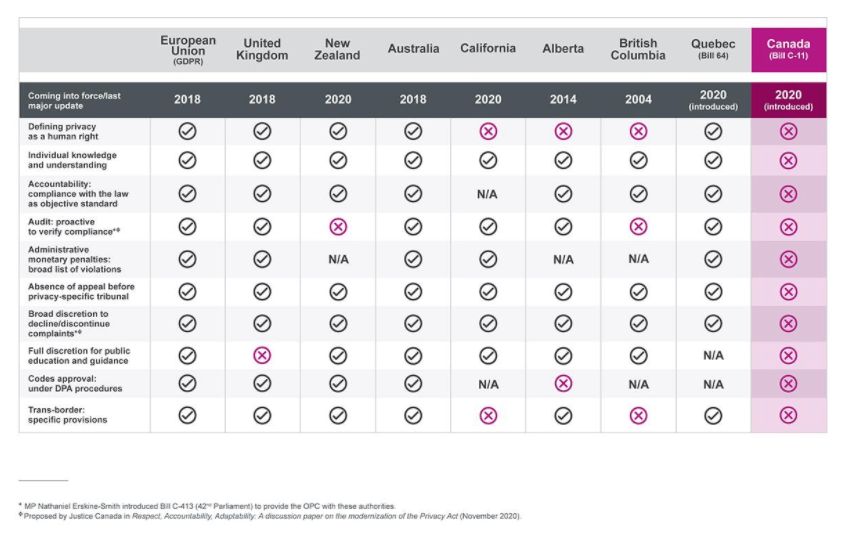

However, a growing number of disparate regulations globally are creating challenges for business leaders and privacy professionals who have to keep up and comply.

With significant privacy regulatory changes under consideration, Canada’s shifting privacy landscape should get the attention of every private sector entity.

Canadians are currently protected by an outdated patchwork of privacy rules, leaving gaps in data protection when using innovative and digital technologies.

While the Federal government – after years of lobbying – introduced The Digital Charter Implementation Act (C-11), the legislation has not been reviewed by a parliamentary committee as of yet.

The journey to privacy compliance

Critics have raised the alarm bells that the new legislation has several weaknesses. Some critics, including the Canadian Federal Privacy Commissioner, maintain that it takes a step backward in privacy protections.

There is a common agreement that Canadian consumers want to have the power to control what personal data they share and how this information will be used.

Especially with the COVID-19 pandemic forcing Canadians to rely almost exclusively on online interactions, it is essential to bring in privacy laws that instill public confidence.

At this point, it seems certain that businesses operating in Canada will need to comply with four different sets of rules in the next few years as provinces remain unimpressed by the proposed federal legislation.

Three bills are now before elected officials: the Federal C-11, Quebec’s Bill 64, and BC’s Freedom Of Information And Protection Of Privacy Act [Rsbc 1996] Chapter 165.

Add to this mix Ontario’s newest consultation on privacy, and you have a challenging journey to compliance for privacy professionals in the next few years.

Canada and EU adequacy

While GDPR compliant companies will have a foundation to address new regulatory requirements, Bill 64, in particular, may be more onerous in several areas.

These include their take on trans-border data flows, confidentiality by default, consent and anonymization provisions.

Ontario’s consultation also points to a more robust approach, as they weave in themes from both the GDPR and CCPA into their thinking.

With Canada’s adequacy with the EU regulations up for review in 2022, much is at stake and C-11 may need a revamp before then.

If Canada was to lose adequacy, entities transferring data from Europe to Canada would need to find a new valid legal mechanism in which to do so.

Critics of C-11, which will replace the federal Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), point to numerous points of weakness:

- its consent framework could allow organizations to collect and use citizens’ data for commercial interests without their knowledge,

- it does not provide special protections for children and youth,

- and its digital rights do not go far enough to protect individuals from new risks.

Read a comprehensive comparison of the two bills.

If amended to satisfy some of the weaknesses mentioned above, Bill C-11 could also recognize and exempt “substantially similar” provincial legislation.

While this would address the disparities between the federal law and that of Alberta, British Columbia, Quebec, and possibly Ontario, the reverse recognition may not happen.

Multiple Canadian privacy regulations present a challenge for companies

Lack of harmonization and mutual recognition will result in significant compliance preparation and complexity for companies operating in those four provinces.

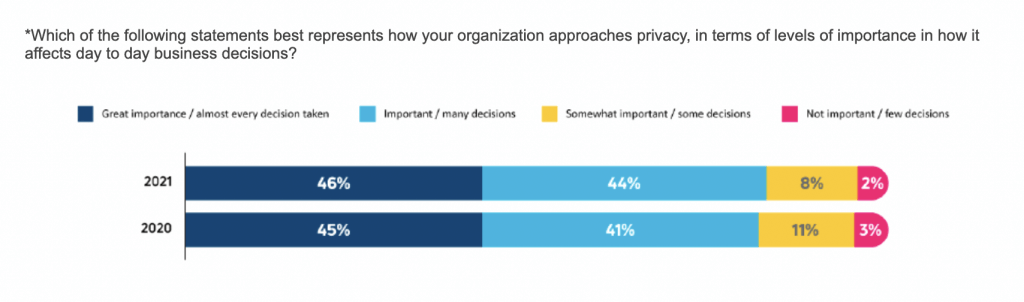

Privacy and data protection are cornerstones of good governance, and most companies view it as very important and embrace it.

TrustArc’s 2021 Global Privacy Benchmark’s Report found that 90% of respondents placed ”importance” or “great importance” on privacy in their business decision-making.

However, a growing number of regulations that are being introduced across the globe are creating challenges for companies as they try to implement new policies while staying abreast of additional developments.

This increasingly complex global privacy landscape requires purpose-built software and automation to manage the various privacy frameworks.

Our survey results illustrate that more and more companies are turning to software for their solutions, particularly purpose-built privacy management software, which saw a seven-point increase year over year.

The opposite was also clear: free/open-source solutions or DIY approaches have declined.

Each of the governments mentioned here have expressed the desire to streamline their privacy regulations and refrain from requirements that would be too onerous to implement.

Yet, the mere fact that there are several different and competing bills that will govern private sector data and privacy requirements creates significant and arguably unnecessary complexity.

Public trust and confidence in data and privacy rights is not just good for consumers but it is also good for businesses.

Governments that adopt a “privacy is a human right” lens to their privacy reforms will not only empower their citizens but will also propel their businesses to be more competitive in the digital age.

Doing so in a coordinated manner across jurisdictions will help with speedy uptake of new requirements and compliance, while avoiding consumer confusion.